Fish in Focus: Christmas Darter, Etheostoma hopkinsi

Christmas Darter, Etheostoma hopkinsi

Stevens Creek tributary (Edgefield County, SC)

Photo by Dustin Smith

Fish in Focus: Christmas Darter

(Originally published in American Currents Winter 2014 by Matt Knepley)

Scientific Name: Etheostoma hopkinsi (Fowler, 1945). In 1963 Bailey and Richards further identified two subspecies: E. h. binotatum of the Savannah River drainage, and E. h. hopkinsi of the Altamaha and Ogeechee River drainages. The former was renamed Christmas Eve Darter, and the latter retained the Christmas Darter name. While the author respects Bailey and Richard’s work, and appreciates their decision to give the two subspecies names that honor their original moniker, he finds no widespread use of the Christmas Eve Darter identity, and herewith respectfully uses “Christmas Darter” and “Etheostoma hopkinsi” inclusive of both groups.

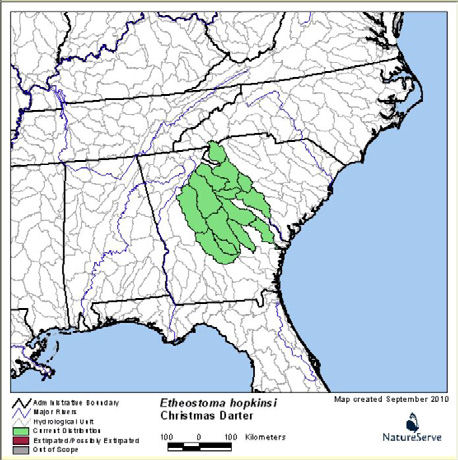

Christmas Darter distribution in North America. Map Source: NatureServe 2013. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer |

The author in his element Photo by Matt Knepley (self-timer) |

Taxonomy: A member of the Percidae family, the Christmas Darter is a close relative of other darters, Yellow Perch, Walleye, and Sauger. Christmas Darters can be confused with Savannah Darters, Etheostoma fricksium. The first dorsal fin is a useful diagnostic. Christmas Darters have a horizontal, brick-red stripe across the middle of the first dorsal fin. Savannah Darters have a horizontal, brick-red stripe along the top edge of the first dorsal fin. Also, Christmas Darters tend to live above the Fall Line, while Savannah Darters live below it.

Christmas Darter, Etheostoma hopkinsi Beaverdam Creek (Edgefield County, SC) Photo by Michael Wolfe |

Meet Etheostoma hopkinsi, the Christmas Darter. Decked out in alternating green and reddish stripes, this is one little fish that appears to have the Christmas spirit all year long. Other decorative elements of E. hopkinsi’s appearance include its two dorsal fins. The base of the first dorsal fin carries a pretty bluegreen hue, which is bordered half way up by a brick red stripe. The second dorsal fin is dull in comparison, the only coloration being brown dashes on the fin rays. Large, fan-shaped pectoral fins may or may not have spots on them similar to those of the second dorsal fin. Christmas Darters use these out-sized pectoral fins to propel themselves through the water, and often employ those same fins to brace the fish against rocks for extra support against the current. Pelvic fins serve to prop it up on the stream bottom. Males of the species are much more colorful. Females wear varying, washed-out looking degrees of the male coloration.

Christmas Darter, Etheostoma hopkinsi Beaverdam Creek (Edgefield County, SC) Photo by Michael Wolfe |

Reaching a maximum length of approximately 2½ inches, this tubular, benthic mini-predator is well designed for the quick flowing, rocky, and riffly streams it calls home. The streamlined shape and small size allow it to dart from place to place, achieving maximum movement for minimum effort. E. hopkinsi have fairly large metabolisms and appetites to match. Hungry Christmas Darters stealthily prowl their swiftly moving waters, stalking the various life stages of aquatic insects that are their primary foods. A wide variety of insects are consumed. If these wee beasties can get their mouths on something, they will try to eat it.

Increasing a darter’s hunting prowess is the curious ability to move their heads almost as if they had necks. Their eyes are also very capable of moving so as to be better able to focus on objects. The fish will slowly and carefully prowl the streambed, searching out insects in the substrate, rocks, and other objects. Upon finding a prospective meal, the darter sneaks up as closely as possible, often turning or lowering its head slightly, establishes a visual lock on its target, arches its back, and pounces. The prey is inhaled so rapidly it can be hard to see happen. A less often employed, yet still common feeding approach is a mad dash in a beeline toward a distant prey item. The target must be worth it though; the added energy expended and the degree to which the darter exposes itself means that not just any prey will be chased down in this manner.

Christmas Darter habitat Little River (McCormick County, SC) Photo by Matt Knepley |

Common water-willow, Justicia americana A frequently occurring (but not required) indicator of Christmas Darter habitat Photo by Matt Knepley |

Christmas Darters are a true southern specialty. Anyone looking for them in the wild will need to stay in the southeast as only South Carolina and Georgia can claim them as native. South Carolina specimens reside in streams of the Savannah River drainage from Oconee County south to the Fall Line near the Edgefield-Aiken county border. They appear to be most common in Abbeville, McCormick, and Edgefield counties. Their territory in Georgia is somewhat larger, occupying major portions of the Altamaha, Ocmulgee, Oconee, Ogeechee, and Savannah River basins in the central eastern part of the state. Searches in these areas, in water moving over shallow, rocky-bottomed riffles and runs with a close proximity to small to moderate amounts of varying aquatic vegetation are the most likely to be successful. While they do like an appreciable current, they appear to avoid the most tumultuous waters. Pounding whitewater is not to their liking.

The Christmas Darter is a very rewarding animal for those who enjoy keeping fishes in aquariums. Not only are they pretty and peaceful, but they also exhibit some interesting behaviors as well. E. hopkinsi will become quite tame in short order. They are curious fish, taking active notice not only of events in their aquarium home, but also in what is happening in the world outside their tank. They often approach the glass to watch the people watching them. It is quite humorous to observe a Christmas Darter approach the aquarium glass, crane its head and train its eyes on its caretaker. They have such personality, and just enough differences in their patterns, that it does not take an aquarist long to be able to distinguish individual animals.

Christmas Darters are quick to associate their keepers with food. This allows the aquarist ample opportunity to view their “sneak and pounce” feeding approach. Small frozen mysis shrimp, frozen brine shrimp, frozen glassworms, and mosquito larvae are readily accepted. Frozen bloodworms are especially relished by these little eating machines. The author has one female that, if allowed, will consume so many bloodworms she’ll have one hanging out of her mouth until earlier prey are digested enough to allow her to swallow it! E. hopkinsi are not shy, and if their tank mates aren’t too aggressive they will soon begin making mad dashes from the bottom to the midwater level to get first dibs on tasty looking morsels. After snagging a meal in this manner, they then extend their fins and glide gracefully back to the bottom. This “sprint and glide” approach becomes the go-to feeding style for many captive specimens. The only food that’s flatly refused is anything in flake form.

The author has no definitive information on this species’ reproductive strategies, but has made the following observations in home aquaria. It appears either sex may initiate spawning. A female may approach a male and position her midsection next to the male’s head, or a male may approach the female and align himself with his anterior half resting on her. The initiating fish will vibrate its front half horizontally. If the other fish is receptive, they will work themselves into a vibrating frenzy that sends smaller pieces of substrate literally flying across the tank. The pair will be moving so rapidly it is hard to make conclusive observations. The male, who will have assumed a position above the female, appears to beat the female very rapidly, but not harmfully, with his pectoral fins. Until he has fry grown out to adulthood (not likely in his community tank), the author can only make the educated guess that this is actual reproductive behavior. Other NANFAns have had success breeding captive Christmas Darters, and hopefully their more concrete experiences will be made available in the future.

Perhaps the most gratifying aspect of keeping E. hopkinsi is that you will probably have to collect them yourself. State regulations regarding collecting change frequently, so make sure you have the most up-to-date information. State Department of Natural Resource websites can provide basic information, and the individuals capable of answering specific questions can be identified there as well. Of course, obtain permission from any landowners on whose properties your collecting takes place. The author has collected Christmas Darters from Beaverdam Creek in Edgefield County, South Carolina, in late January. Neoprene waders kept him toasty warm while he planted his dipnet in the ends of small chutes in ankle to mid-calf deep waters. His daughters stirred up the bottom above the chutes, chasing the darters down into the net. No doubt there are more productive approaches, but the time spent with family and the very intimate familiarity that can be obtained with a stream and its residents makes this approach the author’s favorite. Michael Wolfe and the author seined the same stream in late April 2013, as well as nearby Stevens Creek, and turned up large numbers of Christmas Darters. Stevens Creek specimens tended towards smaller sizes and brighter colors than their Beaverdam Creek counterparts.

While Christmas Darters don’t carry any state or federal listings prohibiting their taking at this time, their limited range in South Carolina does place them on the Species of Special Concern list. Be sure to protect the population of the fish by taking only a small number of them. Transport your catches to their new home in secure containers, and follow standard procedures to acclimate them to their filtered, unheated aquarium. They will be happiest in a tank designed to mimic their natural homes; one with plenty of rocks to explore, some aquatic plants, and a moderately fast current. That said, they are surprisingly adaptive in captivity, and will adjust to most reasonable aquarium conditions.

Given its attractiveness, interesting behavior, and suitability for North American native aquaria, the Christmas Darter is surprisingly anonymous. It is the author’s opinion that they deserve a much larger fan base.